US-China Power Struggle and Its Ripple Effects in Brazil and Latin America

Dawisson Belém Lopes is a professor of international and comparative politics at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and a research fellow of the National Council for Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) in Brazil. He was a visiting academic at the University of Oxford’s Latin American Centre (2022-23) and a SUSI scholar on US foreign policy at the University of Delaware (2021). This article was written by Belém Lopes especially for issue 105 of the WBO weekly newsletter, dated February 23, 2024. To subscribe to the newsletter, enter your email in the field below.

The current geopolitical scenario in Latin America is marked by the intensifying competition between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, the two global superpowers. This essay, crafted from a Brazilian viewpoint, delves into the historical backdrop, evolving dynamics, and collateral effects of this power struggle in the region. From my angle, the situation appears to be highly consequential.

Commencing this analysis with a bold theoretical assertion about Latin America, one can rightfully claim that the region distinguishes itself as the most Westernized portion of the Global South. It exhibits common features with the Occident in terms of religion, language, legal institutions, market capitalism, and representative democracy—a trend that is notably evidenced by Brazil. Building upon this premise, various reverberations may manifest.

Since the early twentieth century, the United States has played a significant role as Latin America’s primary trading partner, surpassing Europe and solidifying its position as the region’s most influential external actor. However, this trend gained further momentum in the twenty-first century when China outpaced the United States as the main export destination for Latin American nations. Unsurprisingly, this foreign policy alternation has brought about myriad implications in this part of the globe where we live.

Latin America, except for Cuba, remained under the umbrella of the United States during the Cold War and chose not to join the Non-Aligned Movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Brazil, albeit consistently adopting a third-worldist foreign policy, especially from an economic perspective, deviated from the Bandung Conference approach by aligning diplomatically with Washington.

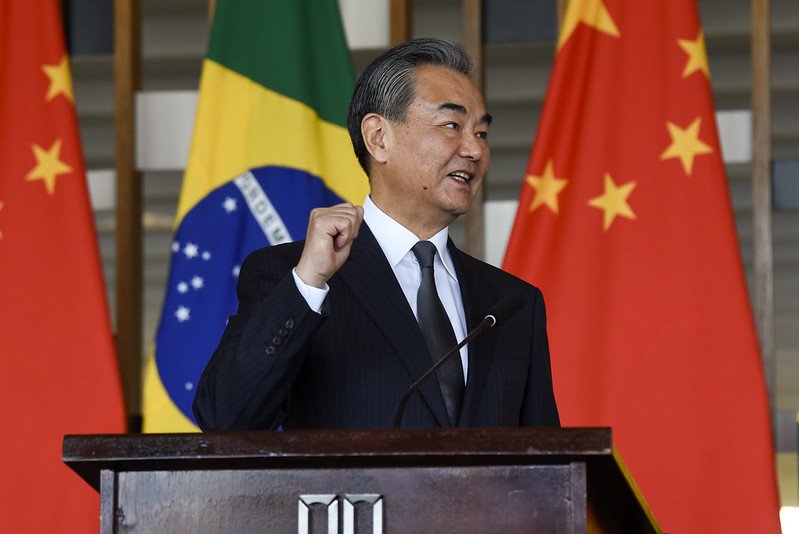

“Brazilian president is navigating with pragmatic ambivalence the US-China arm wrestling while pursuing an autonomous diplomatic approach”

Dawisson Belém Lopes, professor of international and comparative politics at the UFMG

While China has augmented its presence in Latin America through investments and trade bonds over the years, this change has never meant an inexorable retreat in political influence for the United States. Not to mention that Washington maintains a cultural edge in the region: walking through the streets of Managua, Bogota, Asunción, or Rio de Janeiro, one would not observe anything resembling a “Chinese way of life;” quite the opposite.

However, the decline in the US share of global GDP, dropping from 40-45% in 1945 to a meager 14% in 2023, mirrors Latin America’s gradual distancing from White House worldviews. This is evident in voting patterns at the UN General Assembly. In the case of Brazil, during the presidential administrations of Eurico Gaspar Dutra (1946-50) and Juscelino Kubitschek (1955-60), the country’s representatives aligned with American diplomats at a rate of 90%. Nowadays, the convergence percentage between Brazil and the US is not much higher than 25%. This general trend applies to the rest of Latin America as well.

Still, there’s an additional layer to consider. Since the early 1970s, when mainland China replaced Taiwan at the United Nations, Latin America, and Brazil, especially in the context of votes at the UN General Assembly, have shown proximity with Chinese delegates. This connection has a fundamental rationale: both the People’s Republic and Latin American countries have, for decades, shared similar concerns related to development, finance, peace and security, decolonization, international law, and other issues. Such diplomatic like-mindedness cannot be downplayed.

Another crucial factor to note, given the increasing polarization of global affairs, is the assertive position taken by countries like Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico regarding today’s international conflicts, such as those in Ukraine and Gaza. It can be argued that the region is no longer issuing a blank check to the West/US, indicating resistance to unilateral influence. Against this international security background, the waning ability of the United States to co-opt Latin America serves as a cautionary signal.

As the United States and China vie for influence through strategies like friend-shoring (encouraging companies to shift manufacturing away from authoritarian states and toward allies), near-shoring (the practice of relocating business operations to a nearby country), and decoupling (divesting from a country), Brazil and Mexico emerge as net beneficiaries. The United State designates Mexico as its preferred trade partner and investment destination, while China directs substantial investments to, and imports commodities from, Brazil. All in all, both Brasília and Ciudad de México have plenty of reasons to be content with the current state of affairs.

Buenos Aires, on the other hand, faces the risk of distancing itself from Washington and Beijing. Despite the welcoming tone towards the West struck by the recently inaugurated president Javier Milei, Argentina has previously committed to agreements and initiatives, hinting at a pro-China stance. The transition ahead may not play out as seamlessly as Milei’s campaign discourse implied. The ongoing dynamics of the US-China competition will undoubtedly continue to shape the geopolitical future of the nation, and only time will reveal the full extent of its impact.

As Lula’s Brazil resists becoming a merely passive recipient of external influence, the unfolding scenario can signify his third mandate’s litmus test. Accusations of implementing an anti-US or anti-Western foreign policy may be seen in a different light, suggesting that the Brazilian president is navigating with pragmatic ambivalence the US-China arm wrestling while pursuing an autonomous diplomatic approach. After all, proactiveness and self-assuredness should not be misconstrued as a defiant or non-collaborative attitude.