How US Threats to Venezuela Would Affect Brazilian Leadership in South America

By Carolina Silva Pedroso*

If there was any doubt about the hostility of Donald Trump's policy toward Latin America, his speech at the UN General Assembly on September 23 was illuminating. After discussing the alleged threats posed by Latin American immigrants, the US president targeted his attacks on Venezuela. He claimed that the attacks on Venezuelan vessels had blocked the entry of drugs into his country and, consequently, prevented the deaths of thousands of its citizens. In the same vein, he categorically stated that "terrorist" drug trafficking organizations were the “worst gangs in the world.” The message was brief but direct: the escalation of tensions in the Caribbean will continue.

For Brazil, there are at least two major reasons for concern regarding its exercise of regional leadership. The first concerns the fundamental principles of its international presence, such as the peaceful resolution of disputes and the consolidation of a zone of peace within its geographic boundaries. For decades, Brazilian foreign policy has conceived of a natural vocation to lead, if not Latin America as a whole, then South America. Beyond its continental dimensions and economic weight, Brazil shares borders with virtually every country on the subcontinent and has incorporated a conciliatory role into its diplomatic practice to avoid conflicts between its neighbors.

This notion is reflected in the South Atlantic Zone of Peace and Cooperation (ZOPACAS), an initiative to maintain peace in the southern Atlantic Ocean, fostering shared governance to prevent external interference. Although the Caribbean—a region that has been battered by US military equipment—is not strictly speaking part of the South Atlantic, it is geographically very close to this area of peaceful expansion led by Brazil.

Furthermore, this represents a break with the agreement reached at Tlatelolco in 1967, in the aftermath of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, when the Cold War nearly led the world to a nuclear catastrophe. Driven by the activism of the Mexican Foreign Ministry, but also by strong advocacy from Brazil, the treaty prohibited the development of nuclear technology for military purposes in the region. Since then, Latin America and the Caribbean have become a denuclearized zone.

In an additional protocol, it was established that extraregional powers would submit to these terms, which implied that they should not use nuclear weapons against signatory countries. Therefore, the presence of US nuclear submarines, supposedly to combat Venezuelan drug trafficking, is a breach of commitment and jeopardizes the integrity of Latin America as a space free of weapons of mass destruction.

Caracas' immediate response was to activate its defense system, closing airspace, and enlisting civilians to join militias and military training. The asymmetry of forces may, on the one hand, give the impression of a US advantage in the event of a confrontation with Venezuela. On the other hand, history shows that military power is not always decisive for a successful incursion. Maduro seems to know this and is willing to arm military and civilian personnel side by side to defend the country's sovereignty. Once again, historical examples demonstrate that the humanitarian prospects of this type of confrontation are bleak.

Although unlikely, the outbreak of a direct conflict raises the second cause for concern for Brazil. From a practical standpoint, there would be direct effects on the national territory, especially in the northern portion. It is not in the country’s interest to have a possible war so close to a border already crisscrossed by various issues, which would generate greater instability and increased migratory and humanitarian pressure.

“Beyond the direct consequences, Brazilian diplomacy would strive for peaceful solutions”

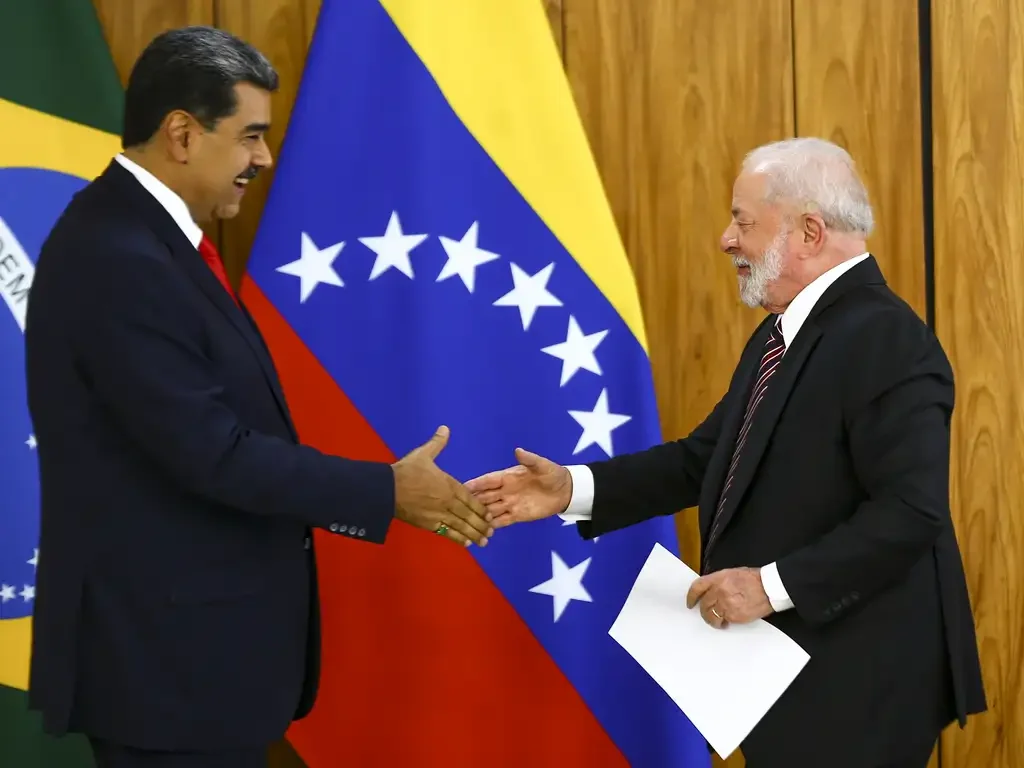

Beyond the direct consequences, Brazilian diplomacy would strive for peaceful solutions, both due to its own institutional tradition and the willingness of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva's government to seek conciliation in various forums, despite Brasília's strained relations with the two main actors in the dispute. If the outcome were positive, the country would be catapulted to an even more prestigious position as a relevant global player.

However, the worst-case scenario must be considered: an overflow of the conflict beyond the Venezuelan Caribbean, the involvement (direct or indirect) of extra-regional powers such as Russia and China, and, finally, the possibility of violent internal power struggles in Caracas. In this case, Brazil's ability to forge feasible agreements in the face of so many areas would be severely tested, with risks of profound damage to its mediating role at the regional and global levels.

As with any hypothetical exercise, the prospects tend to seem exaggerated. However, in a turbulent world, it is legitimate to question Brazil's ability to exercise peaceful regional leadership. The presence of nuclear weapons in the Caribbean is like a spark in a flammable area, but whose combustion potential could be neutralized by the Fire Department. It remains to be seen whether Brazil would have all the necessary skills and resources to perform this noble role in such a challenging context.

*Carolina Silva Pedroso is a professor in the Department of International Relations at the Paulista School of Politics, Economics, and Business at the Federal University of São Paulo (EPPEN-UNIFESP) and a researcher at the National Institute of Science and Technology for Studies on the United States (INCT-INEU).