Relations between Brazil and India from the Multilateral Nexus: From the Bandung Conference to the 2025 BRICS Summit

By Matheus Petrelli*

The BRICS summit, held in Rio de Janeiro in June 2025, focused media and public attention on the contemporary debates that permeate the dynamics of the international system. With approximately 50% of the world's population and approximately 40% of global GDP, the bloc, comprised of Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Iran, Indonesia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates, presents itself as a new center of international power and influence.

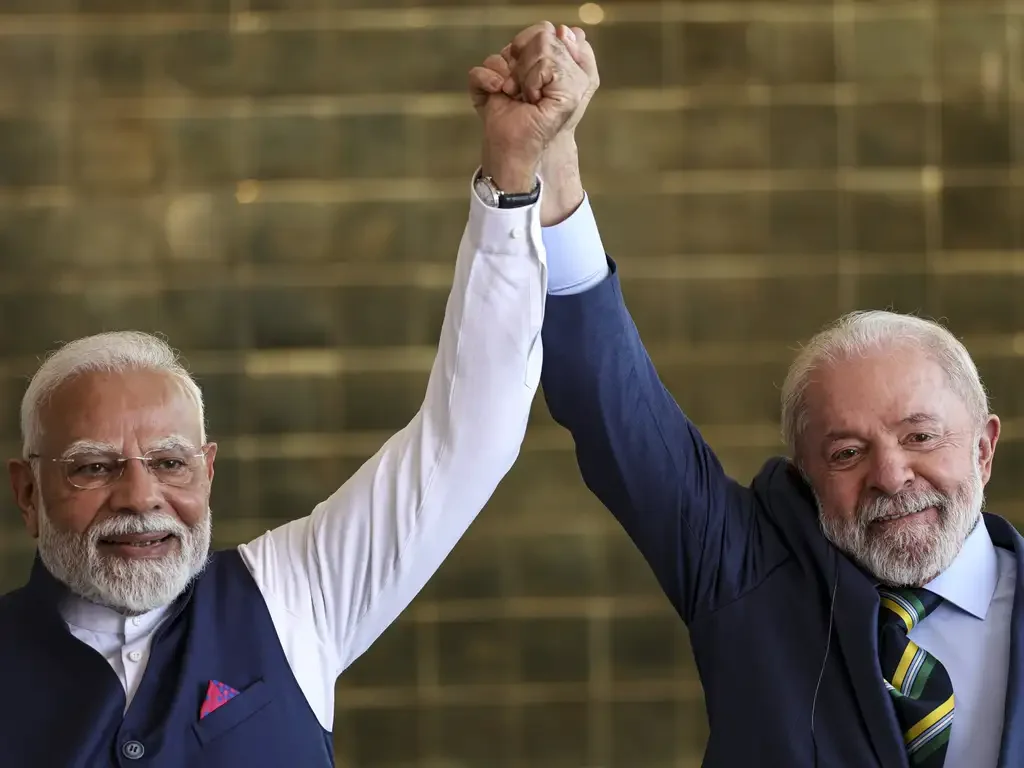

In addition to the diverse commitments agreed upon, the event promoted meetings between various national leaders. Among them, the presence of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi went beyond the summit. Invited for a state visit to Brasília following the bloc's event, the Brazilian government took advantage of the Indian leader's stay in Brazil to expand political dialogue and deepen cooperation with India. Given the growing importance of BRICS and Indo-Brazilian relations, understanding their history is essential.

Although diplomatic ties officially began only in 1948, the ties between the countries date back to pre-colonial times. Pedro Álvarez Cabral, upon arriving in Brazil, sought alternative routes to reach the valuable spices found in Asia—or the "Indies." Furthermore, although most of India was invaded by the British, Portugal was responsible for colonizing a portion of India. The Portuguese state in India comprised regions near Goa, Damião, and Diu, in the southwest of the subcontinent. Although the country gained independence in 1947, Portuguese rule continued until 1961.

Given the particularities of each process, like Brazil, India also suffered from Portuguese colonialism. In addition to all the parallel consequences generated by the colonial process, the Indo-Brazilian relationship began in a turbulent state, also curtailed by the colonizing metropolis. After gaining independence from the United Kingdom, India was still fighting for territories controlled by the Portuguese state. During the negotiation process, a diplomatic rupture occurred between the Indian Union and the Portuguese government. As a result, the European country requested that the Brazilian government assume official representation of Portuguese interests. With a position of unconditional support for Portugal, Brazil's stance generated disappointment and dissatisfaction in India. This scenario began to change during Juscelino Kubitschek's term, with the increased Brazilian interest in the Afro-Asian market. The milestone of this rapprochement with India was the meeting between Brazilian diplomat José Cochrane and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in Delhi in the early 1960s.

Parallel to its national struggle, India was one of the countries that championed the agenda of people's self-determination and decolonization internationally. It was with this in mind that, in 1955, the Indian government, as one of the organizing members, participated in the Bandung Conference. This meeting, known as one of the precursors of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and Third World associations, was extremely important in a context of competition for international influence between the United States and the Soviet Union. This context of bipolarity marked another divergence between Brazil and India. While the former—largely due to its geographic position and the geopolitical influence exercised by the United States in South America—aligned itself with the Western bloc, the Indian government—despite holding leadership positions in the NAM—mainly maintained closer relations with the USSR. Despite their relatively opposing positions, due to their convergence on agendas such as the right to development, self-determination of peoples, and decolonization, India unofficially invited Brazil to become a full member of the NAM. At the movement's second summit, held in 1961, the Brazilian government participated as an observer, but limited itself to that position.

Shortly thereafter, the convergent agenda of defending the right to development returned to the center of Indo-Brazilian relations. In 1964, the creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) arose from the demands of countries such as Brazil and India, which desired the establishment of a permanent international forum focused on the development agenda. This resulted in the establishment of a new body within the United Nations (UN), which, in addition to representing the political power of the then-third world, served as a forum for increased coordination between these countries.

Thus, at the end of the first UNCTAD conference, 77 developing countries signed a Joint Declaration seeking to promote South-South cooperation. Thus, the G77 was formed.

This entire context of creating multilateral environments for cooperation between developing countries was essential for the strengthening of the Indo-Brazilian relationship. The convergence of the two countries on this agenda led to joint positions being articulated on several occasions. In addition to UNCTAD and the G77, another common ground between Brazil and India was their opposition to the 1967 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Described by then-Brazilian Foreign Minister Araújo Castro as a freeze on global power and, by the Indian government, as nuclear apartheid, the proposal was sharply criticized by both countries.

Although the Cold War brought the countries closer together primarily on the development agenda, it was after its end that Brazil and India fostered closer ties. With the dissolution of its main commercial and military ally—the USSR—the Indian government, beginning in the 1990s and 2000s, had to reinvent its foreign policy. In parallel, the September 11, 2001, attacks prompted the United States to seek rapprochement with India. The US's war-on-terror foreign policy and Washington's increased strategic interest in Pakistan—India's historic rival—allowed Delhi to reinsert itself into the dynamics of the post-Cold War international system.

Despite its ties to the United States, Indian foreign policy remained aligned with the defense of its core agendas. With the aim of promoting trade integration, reducing international inequality, and other South-South cooperation agendas, the IBSA Dialogue Forum was created in 2003, again based on Indo-Brazilian convergences.

This time, in addition to Brazil and India, South Africa joined the group, representing, once again, a mechanism that reflects the defense of common agendas between the Brazilian and Indian governments, such as social development.

Continuing the process of rapprochement, the following year, in 2004, Brazil and India, along with Germany and Japan, formed the G4. The coalition, which sought reform of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), advocated for an increase in the number of permanent seats. Since the end of World War II, the UNSC has consisted of 15 countries. Of these, five are permanent—China, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Russia—and ten are rotating, with two-year terms. Arguing that the council lacked the representation required for the international dynamics of the 21st century, the G4 proposed that the four countries, along with two others elected by the African Union, become permanent members of the UNSC. Although the coalition has not yet achieved its objective, the presence of Brazil and India once again demonstrates the alignment between their foreign policies and the prominent role of countries in the global South.

In the same decade, in 2006, a new and significant chapter in the Indo-Brazilian relationship began. In addition to the signing of the Strategic Partnership between the two states, on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), the first BRICS meeting took place. The acronym formed from the initials of Brazil, Russia, India, and China was chosen as the name for the cooperation forum between the countries. After the 2008 economic and financial crisis, which primarily affected the central countries, the four founding states began to seek coordinated action in multilateral forums such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the G20. Aiming to adopt more prominent international positions, BRIC—which became BRICS after South Africa joined in 2011—began to act as one of the most influential representations of the Global South in the international system. In 2009, the same year as the first BRICS Summit, during COP15, Brazil, South Africa, India, and China established BASIC. The bloc, whose main purpose is to strengthen the debate on climate-related agendas, is another multilateral forum in which the Brazilian and Indian governments articulate their foreign policies.

Therefore, after introducing the main international cooperation forums between Brazil and India, it is possible to observe the existence of historical political and economic convergences and a growing relevance. Despite the troubled beginning of their bilateral relations, the defense of the right to development, especially within the framework of the creation of UNCTAD, the G77, and opposition to the NPT, demonstrates that, even close to opposing powers – the USA and the USSR – the countries managed to converge, to a certain extent, on their international agendas. The articulation of these countries, previously marginalized in the bipolar dispute, has given them increasing international relevance. More recently, since the 2008 crisis, the new dynamics imposed by trade and political disputes between the United States and China, the war between Russia and Ukraine, and the various conflicts around the world have reaffirmed the relevance of the Global South to international dynamics.

The current context presents a trend of transition from a practically unipolar system – under direct or indirect US leadership – to a multipolar one. In this new scenario, blocs that bring together the main emerging powers, such as IBSA, G4, BASIC, and BRICS, are increasing their members' international influence. The 2025 BRICS summit, held in Brazil, for example, marked the members' commitment to multilateralism and global governance reform. Countries like Brazil and India, which are seeking greater prominence and converge on diverse agendas, use these blocs and coalitions to achieve more prominent positions in the international system's decision-making process. Thus, understanding the history of the Indo-Brazilian relationship becomes essential for analyzing the present and, even more so, for projecting new partnerships in a future in which the global South gains increasing relevance.

*Matheus Petrelli is a master's student in International Political Economy at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and holds a bachelor's degree in Defense and International Strategic Management from UFRJ.